Stocks and bonds gain when Fed policy becomes more accomodative.

Main Points:

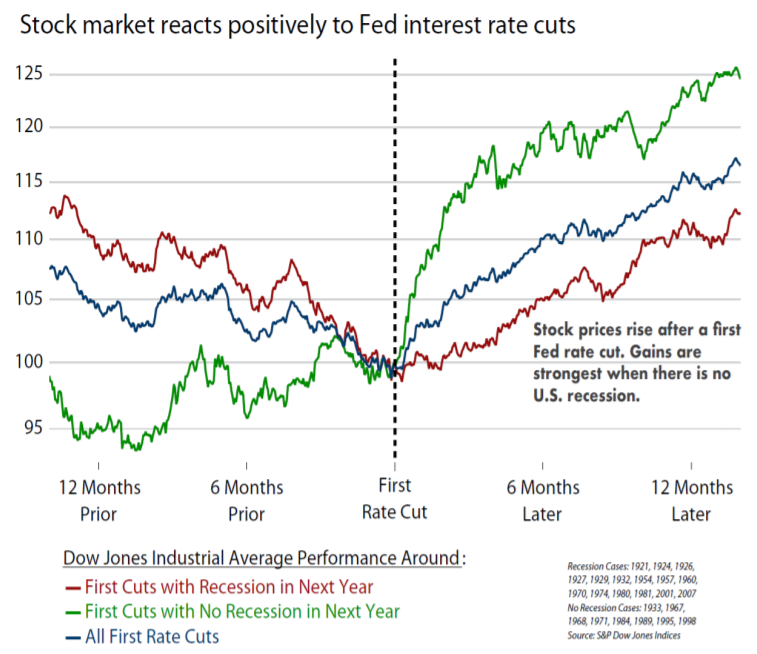

- U.S. and international stock prices rise after a first Fed rate cut. Gains are strongest when there is no U.S. recession.

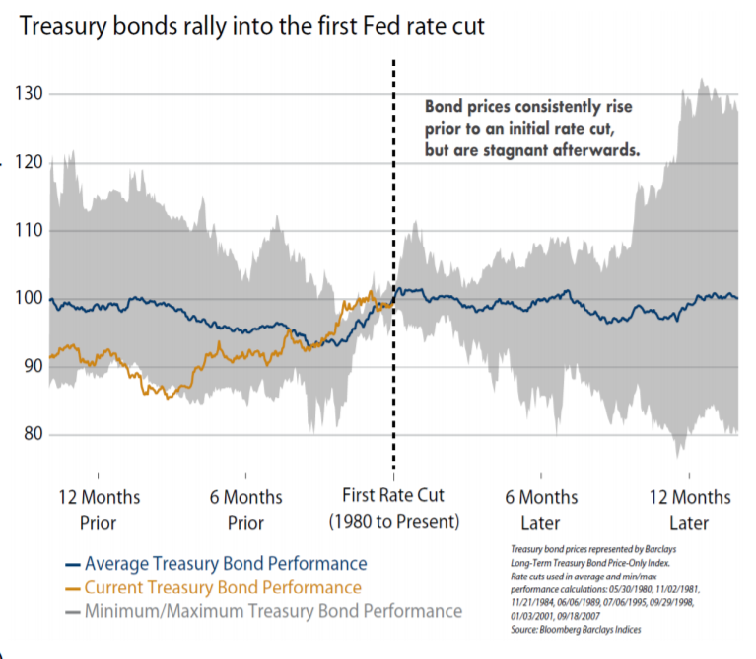

- Bond prices consistently rise prior to an initial rate cut, but are stagnant afterwards.

- Rate cuts can help boost economic growth, but are more effective during recessions.

The worst kept secret in Washington, D.C. was that the Federal Reserve was cutting interest rates. On July 31, the Fed reduced the discount rate by 0.25%. The last rate cut was in December 2008 amidst the financial crisis. So what does a rate cut mean for markets?

The stock market's reaction to an initial rate cut is bullish. The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) has climbed an average of 16% in the year after the first cut. In fact, the DJIA has risen in 18 out of 23 cases since 1921.

However, recessions matter. The Fed lowers borrowing costs for a reason: economic conditions are deteriorating. The DJIA has been stronger, on average, when a U.S. recession did not occur within a year of the first cut. U.S. recession risks are low and the market is tracking closely to the non-recession cases.

In the year before the first cut, the DJIA was up an average of 6.6% in nonrecession cases and down 7.1% during recession cases. In the year after the first cut, the nonrecession cases continued to shine, with the DJIA up seven out of eight times by an average of 23.8% (chart below).

In the recession cases, the DJIA still gained 10.6% in the year after the first cut, less than the nonrecession average, but well above the long-term average annual gain of 6.1%.

Dividend stocks have tended to outperform non-dividend paying stocks by 5% one year after the first rate cut. Furthermore, the fastest dividend growers outpaced the highest dividend yielders. International stocks also like the first Fed rate cuts, as they gained an average 5% one year later. Again, US. recessions mattered. The largest market gains were after the 1995 and 1998 rate cuts.

The bond market correctly anticipates the first Fed rate cut. Long-term Treasury yields have fallen in every case back to 1970 in the months leading up to the first rate cut. Treasury bond prices tend to bottom 2-3 months before the rate cut and stabilize after the rate cut (see chart).

Treasury bonds generally stagnate after the first rate cut. In the four cases since 1998, there has been a tendency to "buy the rumor, sell the news" around the first rate cut. Investment grade bonds performed well heading into the first cut, but high yield and Emerging Markets bonds struggled in 1998, 2001, and 2007. Bond sector results were more mixed following the first cut.

The yield curve (the difference between longer dated yields like Treasuries and shorter ones like T-bills) has steepened in every case in the months leading up to the first rate cut. The curve tends to steepen for another month after the cut. This is good for bank stock performance, as a steeper yield curve boosts profits. Since 1954, there have been 16 instances of first Fed rate cuts, most of which have turned into easing cycles. Nine of these cases had either taken place during a recession or had been associated with recession within a 12-month period.

Rate cuts can provide a boost to the economy. In past cases, U.S. real GDP growth on a year/year basis was typically slowing ahead of the first Fed Rate cut, but stabilized within a year after the cut. A Fed rate cut can support consumer spending, which represents two-thirds of the U.S. economy, through increased confidence and a positive stock market wealth effect. On average, the global ex-U.S. central bank policy rate has peaked at around the same time that the Fed has initiated rate cuts.

Since the world's economies are interconnected, it makes sense that economic weakness in the U.S. would be evident in other parts of the world, thus prompting easing policies from other central banks. Fed easing also often relives currency depreciation risks from many economies. This allows some central banks to become more accommodative. The interconnected relationship is occurring in the current cycle.

After the Fed adopted a more friendly tone in January of this year, several emerging and developed market central banks shifted their policy from tightening to easing. These included central banks in India, the Philippines, Malaysia, Chile, Iceland, Australia,and New Zealand. Other major central banks, such as the ECB, BoC, AND BoJ, have adopted a friendlier tone, but rates have not yet been reduced as of this month.